A European Space Agency satellite, ERS-2, is anticipated to reenter Earth's atmosphere and largely disintegrate on Wednesday morning.

The agency's Space Debris Office, in conjunction with an international surveillance network, is closely monitoring and tracking the Earth-observing ERS-2 satellite, slated for reentry around 11:32am ET on Wednesday, with an approximate 4.5-hour window of uncertainty. Regular updates are being provided on the ESA's website.

Due to the "natural" nature of the spacecraft's reentry, without the capability for manoeuvres, its precise entry point and time are indeterminable, as stated by the agency.

Read more: ERS-2 — ESA's insight into the dead satellite's return to Earth

Solar activity, which can alter Earth's atmospheric density and affect how it interacts with the satellite, adds to the challenge of pinpointing the exact reentry time.

With the sun nearing its peak in the 11-year solar cycle, known as solar maximum, anticipated later this year, increased solar activity has already accelerated the reentry of ESA's Aeolus satellite in July 2023.

How hard could ERS-2 hit the Earth?

Weighing an estimated 5,057 pounds (2,294 kilograms) after fuel depletion, the ERS-2 satellite is comparable in size to other space debris reentering Earth's atmosphere weekly, according to the agency.

It is expected to disintegrate around 50 miles (80 kilometres) above Earth's surface, with the majority of fragments burning up. Any potential remaining fragments are not anticipated to pose risks as they are unlikely to contain harmful substances and are expected to fall into the ocean.

About ERS-2

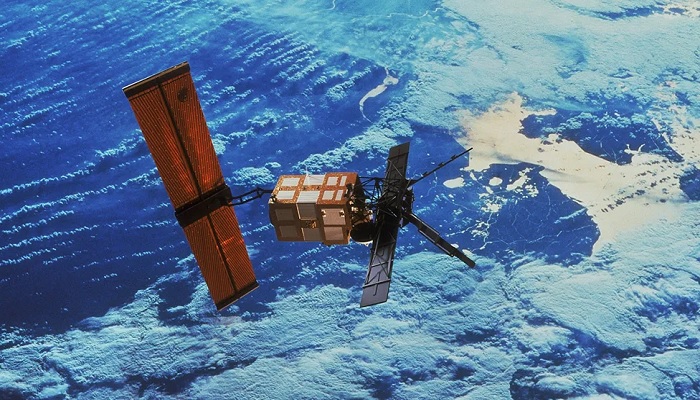

ERS-2, launched on April 21, 1995, alongside its twin ERS-1, was a groundbreaking Earth-observing satellite, gathering crucial data on polar caps, oceans, land surfaces, and natural disasters until its retirement in 2011.

The decision to deorbit ERS-2 aimed to prevent contributing to space debris. After a series of deorbiting manoeuvres, the satellite was placed on a trajectory to reenter Earth's atmosphere within 15 years.

The likelihood of an individual being harmed by space debris annually is exceedingly low, significantly less than the risk of domestic accidents, according to the agency.